ANDY WARHOL MEETS THE MAN OF STEEL

The sordid history of comics and art

by Ali Fitzgerald

To distinguish between comic and “high” art is equivalent to art fascism these days. Is there such a difference between a comic panel of Wonder Woman and a painted comic panel of Wonder Woman? Auction results and sales figures suggest that this is a real and relevant hierarchical gap rather than a passing semantic slip. The painted Wonder Woman is a luxury commodity while the comic Wonder Woman exists mostly in print, a medium still made for and, arguably, by the masses.

Early comic artists had such a cavalier relationship towards “objets d’art” that original panels were often thrown in Manhattan dumpsters after printing. With the exception of the recent Chelsea galleries whose inventories were severely damaged during Hurricane Sandy, throwing art in the streets is still sacrilege in the high art world.

In the years following the Second World War, artists like Warhol and Lichtenstein borrowed from the language of pulp comics but operated within a very different system from their comic contemporaries like Jack Kirby and Neal Adams. Warhol’s world was populated by collectors, gallerists, dealers, and finally, a monolithic singular artist or collective whose work invariably belonged to them. In contrast, Dick Sprang, who drew Batman for almost twenty years, was never allowed to sign his own name because of the anonymity demanded of comic artists.

Jeff Koons, 'Triple Popeye', 2008

Gabe Fowler, owner of Brooklyn comic book store Desert Island, told me a story about Gabrielle Bell, a mid-level comic artist living in Brooklyn who has authored several books and has a fairly extensive fan base. In her autobiographical comics, Bell laments her career choice, details the plight of the underpaid comic artist and pines for the stability of a bank job. She recently began offering Skype portraits to her fans for thirty-five dollars apiece.

Fowler claims, however, that in ten years comic fans “will no longer be able to afford a drawing from their favorite comic artist.” He thinks the financial chasm between comics and high art is shrinking because it is, rightfully, out of date and based on outmoded systems of production. But what about those early comic pioneers whose work was appropriated for wild financial gain – the lost generation of comic innovators?

While Warhol was disrupting ideas of ownership, Siegel and Shuster were fighting a losing battle to regain the rights to their brainchild, Superman.

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the Mid-West teenagers who created Superman, are hardly household names. But the white-haired provocateur Andy Warhol, who featured superman in his “Myth” series, is dutifully remembered with museum retrospectives and a wealth of critical writing dedicated to his rich artistic legacy. While Warhol was disrupting ideas of ownership and borrowing freely from the wider cultural consciousness, Siegel and Shuster were fighting a losing battle to regain the rights to their brainchild, Superman. They eventually lost, but did finally receive a modest settlement from DC comics in 1975.

With Roy Lichtenstein as their ringleader, pop artists were perhaps the most shameless Ben-Gay bandits. Lichtenstein’s work had a cropped, salacious appeal, forging a new kind of pulp comic aesthetic. His unaccredited source material was lifted from the panels of great comic artists like Jack Kirby and Tony Abruzzo. Kirby once said that his creation, Captain America, “symbolized the American Dream.” For artists like Lichtenstein, a stylized, distilled American spirit was a very potent force.

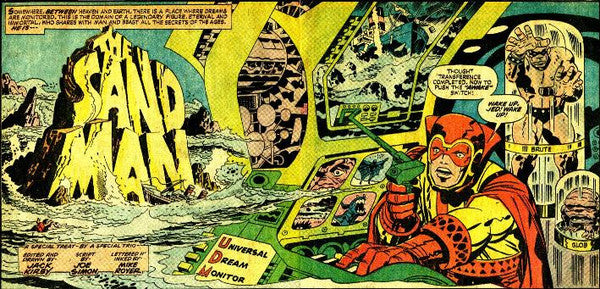

Jack Kirby, 'Sandman Series', 1974

Popeye was another post-war favorite, perhaps because of his squinting, smoking, “every-man” appeal. Jeff Koons, who follows his own brand of Warhollian art morality, began his “Popeye” series in 2002. Koons depicts the bulging limbs of the sailor both in paint and steel, comparing Popeye’s self-created and optimistic nature to that of his own father.

Pop artists wielded the comic aesthetic as a bright, leveling sword, depersonalizing their own work in favor of a reflective, American sheen. But more recently artists have used comic imagery and tactics as social satire. At their best comics can be a pulpy and popular, sometimes vulgar, mirror into our cultural consciousness, appealing to our baser Freudian natures. In her infamous 1996 painting 'Wonder Woman', Nicole Eisenman has Disney’s Alice in Wonderland performing a very difficult and dangerous sex act on Wonder Woman.

Many people argue that the difference between comics and art has something to do with abstraction: the separation of form and meaning. But since the latter half of the twentieth century, the comic medium has been pushed into less narrative and more experimental territories. Fowler has many non-narrative comics at Desert Island, although predictably, they are not his top sellers.

Roy Lichtenstein, 'Look Mickey', 1961

Of course there are artists that straddle the comic-art divide, staking out new territories in a briskly changing cultural panorama. Gary Panter, who started out with rabidly experimental comics and trippy set design for Pee-Wee’s Playhouse eventually settled into a more painterly practice, exhibiting his large-scale acrylic paintings at Fredericks and Freiser.

There are also comic artists like Charles Burns or Chris Ware whose work is given critical recognition and museum exhibitions. A recent talk in Berlin with Chris Ware sold out easily, confirming Ware’s status as a comic superstar. This indicates perhaps a growing respect for the field, alluding to a brighter and more audacious future for comics.

The archetype of the forgotten comic artist as a hard-working social pariah and company man is slowly expanding into a more exciting reality, one that rewards cross-disciplinary efforts and recognizes the freedom and agency of the creator.