EDO POP

The Artful high and low culture of contemporary Japan

by Ana Finel Honigman

Takashi Murakami’s love of Manga, hip-hop and designer labels; Daido Moriyama’s black and white photographs of noir street-life; the pornographic sublime of Nobuyoshi Araki and Mariko Mori’s vision of a bright, shiny future all owe hefty debts to the history of Ukiyo-e.

Few genres from art’s history are as evergreen as Japan’s Edo-era Ukiyo-e prints. “Ukiyo-e” literally translates as "pictures of the floating world,” a phrase signifying the genre’s attention on fleeting beauty. Transiency has been a subject of Japanese art since Ukiyo-e was established in the 17th century and remains a defining theme of Japanese art and culture. The scenes of seedy sex, pop-culture trends, conspicuous consumerism, turbulent romance, cursory moments of tranquillity and ephemeral beauty depicted in Ukiyo-e are faithfully resurrected by today’s leading Japanese artists.

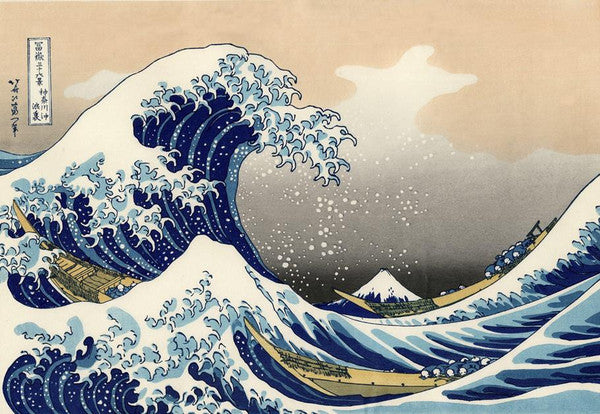

Katsushika Hokusai, 'The Great Wave off Kanagawa', 1829–1832

At its inception, Ukiyo-e wood-block prints functioned as precursors to snapshot photography. The prints themselves were mass-produced and easily disseminated, their ease of creation complementing their subject matter which resonated with Japan’s burgeoning youth-culture. Young urbanites, with limited funds, collected the prints while wealthier patrons bought paintings. Whereas Western art from the same era glorified grand subjects and the notion of art’s immortality, Ukiyo-e drew attention to the era’s equivalent of pop-culture.

The Edo period, which concluded when the arrival of American battleships in 1853 forced the end of self-imposed isolation, introduced a new creative and consumer culture to Japanese society. Edo was the era of Kabuki theater, Suma wrestling, Bunraku puppet theater, poetry, geishas and sexual experimentation. Ukiyo-e represented these creative forms and promoted their beauty to a wide audience.

Takashi Murakami, 'Tan Tan Bo', 2001

These prints are also widely recognized as important influences on French artists of the 19th century: Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh were especially keen collectors of prints by the genre’s masters such as Torii Kiyonaga, Hiroshige and Utamaro. The era’s blend of high and low culture, sexual display and sub-cultural development can also be seen as a precursor to today’s post-modern society.

The coquettish transvestite monk in Okumura Masanobu’s 17th century “Wakashu in the Guise of a Komuso,” for example, is an elegant ancestor of the hairy-chested leering man who Daido Moriyama photographed wearing full geisha-gear. Their attire is almost identical although Masanobu represented his model as a comely beauty whereas Moriyama depicts his subject as grotesque. Moriyama’s disgust with his subjects implies his tastes or politics are actually more conservative that his Edo-era forefathers. The primary difference between Masanobu and Moriyama is not the world they represent but their attitudes towards it. Masanobu lovingly focuses on the charm, freedom and beauty of his contemporary culture whereas Moriyama cynically revels in its grime and depravity.

Takashi Murakami embodies a pure Ukiyo-e spirit with his jubilant embrace of contemporary sexual and consumer culture.

Takashi Murakami, on the other hand, embodies a pure Ukiyo-e spirit with his jubilant embrace of contemporary sexual and consumer culture. Murakami’s “super-flat” presentations of joyfully ejaculating cartoon boys, big-breasted porn-star dream dolls and bright brand labels would have appealed to Edo audiences. Although Murakami’s eye-popping pastel and neon palette, as well his adherence to the Eurasian beauty ideal propagated in Anime, would be alien to historical Japanese audiences, his work’s consumerist focus on novelty and entertainment would be utterly familiar. When he began exhibiting globally, Murakami’s marriage of art and fashion unsettled and shocked Western audiences. Yet, when viewed through the lens of Ukiyo, his art appears rooted in a Japanese tradition.

Nobuyoshi Araki, another of Japan’s more controversial contemporary creative exports, is also grounded in history once his work is compared with Masanobu’s and his peers’ pornographic prints. Masanobu’s prints established the vocabulary for bijinga, Japan’s early equivalent of pin-ups. Literally translating to "beautiful women," the bijinga subgenre of Ukiyo-e revealed geishas in “private moments” as well as with lovers.

Daido Moriyama, 'Untitled' (male geisha), 1968

Many of Masanobu’s prints were fully pornographic yet his bijinga focused on his model’s intimacy and adoring gaze – evoking easy comparisons with Pierre Bonnard’s portraits of his bathing wife or the dreamy nudes of Oui Magazine. Yet, his more extreme images of intercourse can be compared to Araki’s portraits of young models bound in intricate bondage. Alongside fellow Ukiyo-e artists Utamaro, Suzuki Harunobu, Itō Shinsui, Toyohara Chikanobu and Torii Kiyonaga, the bijinga glorified geishas’ ritualized, cultivated allure.

Yet, surprisingly the most striking manifestation of the Ukiyo-e aesthetic and ethos can be seen in the otherworldly science-fiction fantasies of Mariko Mori. Like the intergalactic princesses of sci-fi comics and countless comic-cons, Mori captivated international attention when she dressed as a sex-bot posing outside a toy store. For her 1994 performance “Play With Me,” she fashioned herself as a factory-made creature from the future but her costume’s design recalled the elaborate attire of traditional geishas. The basis for her vision is an extreme combination of Eastern mythology, Western pop-culture and Ukiyo.

Mariko Mori, 'Play with Me', 1994

Mori’s later projects, including “Oneness” which invited viewers in 2002 to recline inside a glittering 6,000kg orb, glorified hopes for a peaceful and transcendental future. The colors and curves of this extraordinary structure evoked the waves and heavy cherry-blossoms of Katsushika Hokusai’s iconic prints, drawing attention to Edo era art.

The work of today’s leading Japanese artists reveals that Ukiyo-e can be credited as the birth of an expressive style and conceptual interests that still dominate imagery from Japan’s forward-thinking art and culture.